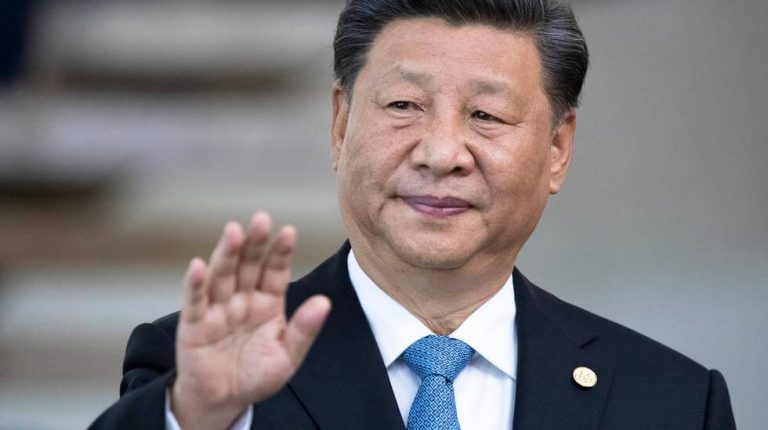

It is a certainty that the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, will be confirmed in office at the 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, currently being held in Beijing. At 69, Xi is also tipped to become the CCP chairman.

In China there is a very close relationship between party and state – the two are often wrongly considered to be essentially the same. This sometimes leads to confusion in western commentary about the powers of different offices and the titles that leaders hold. The current Chinese president is also the general secretary of the Communist Party but, in the past, the head of state was not always the most powerful CCP leader. For example, during the leadership of Mao Zedong, a rival figure, Liu Shaoqi, was president between 1959 and 1966.

Western commentary often sees leadership tension as a starting point for political analysis. In studies of the USSR, “Kremlinology” became a refined art over many decades but it told us little about the fault-lines of Soviet society. What looked like a powerful regime, sending astronauts into space and exploding nuclear bombs, suffered a prolonged crisis of legitimacy in many parts of the society. Keeping the focus on leadership politics will not help explain China.

In contrast with the USSR, the CCP has been able to achieve many of the benefits of modernisation and economic growth without loss of popular legitimacy.

Term limits

The term limits for the Chinese presidency were withdrawn in 2018. It is possible that Xi will be the Chinese leader for many years to come. He is about ten years younger than the president of the USA, Joe Biden.

An article in the Financial Times in late August seems to have been the prompt for speculation about reviving the role of chairman. Mao adopted the title before 1949, when he was consolidating political power during the war against the Japanese occupation. Xi’s anti-corruption drive is seen by the FT as a confirmation of power. The argument is that Xi will become “Chairman Xi” to confirm his status.

There are no formal term limits for officeholders in the CCP, although it has been unusual for anybody approaching 70 to take on a larger role. We may now see a significant development but a change which would be mainly symbolic because Xi is already the most powerful man in China.

Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s modernisation and “opening up”, was the paramount leader without ever being president or chairman. Hua Guofeng succeeded Mao as CCP chairman, but it was Deng – appointed vice-chairman in 1977, who led China. The post of chairman was abolished in 1982 and most functions were transferred to the revived post of general secretary, which is currently held by Xi.

The most interesting question is not about titles but about policies. It would be a mistake to believe that a change of title will make Xi more like Mao Zedong. Mao repudiated many features of the Chinese past whilst Xi celebrates them. Xi Jinping, more than any other leader in China since 1949, consciously connects the past, present and future. He seeks legitimacy by celebrating the revolutionary role of the CCP in restoring China to the status of a world power and by modernisation of the economy and society.

Leadership styles

Xi and Mao also differ in their leadership styles. Xi Jinping has no inclination to use the mass mobilisation campaigns that Mao promoted. Not only did Mao cause chaos in the country with his “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” between 1966 and 1976, he also used the same approach in the previous decade when landlords’ estates were seized as part of the Land Reform programme and the 1958 rapid industrialisation programme, the Great Leap Forward.

Mao’s leadership, before and after 1949, was marked by the “Red versus Expert” tension between intellectuals and ideologues. Xi requires loyalty and expertise. Mao’s style was revolutionary, Deng brought prosperity, Xi stands for prosperity plus stability.

In Chinese official documents – and still more in informal discourse – Mao is seen to have made increasingly serious “errors”. His Cultural Revolution was directly criticised by the party in 2021 in its “Resolution of the Central Committee of CCP on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century”. This stated that the Cultural Revolution had been “catastrophic” and had resulted in “ten years of domestic turmoil which caused the Party, the country, and the people to suffer the most serious losses and setbacks since 1949”. It was, the resolution said: “an extremely bitter lesson”.

The worst excesses of Mao’s time came more than 50 years ago when China was still very poor by international comparison. Since then the overwhelming majority of Chinese people have become healthier, wealthier and much better educated. They see continuity of leadership, and strong connections to cultural traditions of unity, hierarchy, orthodoxy as a vital underpinning to “common prosperity”. China now presents 2035 as the date by which socialist modernisation will be “basically realised”.

If Xi can lead China towards the promised future, and the centenary of the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in October 2049 will be the target date, he will continue to be in a strong position – whether he is chairman or not. Xi, and the party he leads, are focused on the future. He may even still be part of the leadership in 2035 and it is possible that he will be alive in the centenary year of the PRC.

Source: The Conversation

By: David Law, Academic Director: Global Partnerships, Keele University