Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s decision to embark on a diplomatic offensive to outflank China in the Pacific within days of being sworn in has yielded what appears to have been an early success.

Whether Wong’s intervention gave Pacific leaders pause about a wide-ranging economic and security pact with China or they would have baulked anyway, the fact is Australian diplomacy can claim a dividend. In the process, the country appears to have a new foreign minister who will engage in more creative and activist foreign policy then her predecessor.

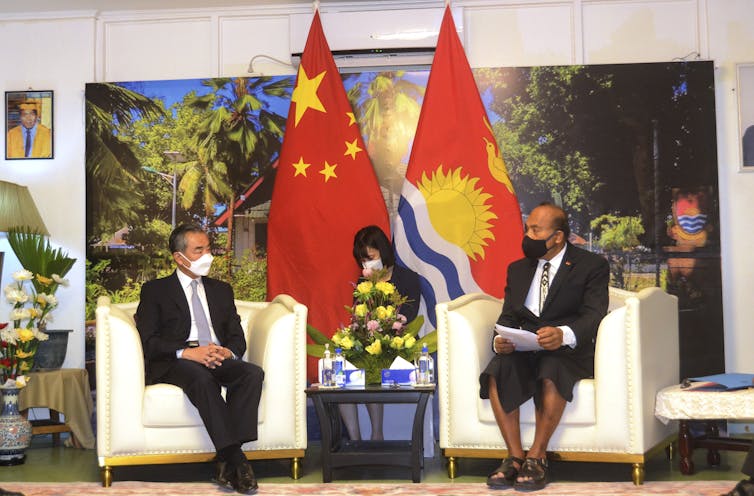

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s extensive tour of the Pacific has been aimed at extending Beijing’s influence in the region at a moment when regional leaders had grown restive about Australia’s commitment to its immediate neighbourhood.

The Morrison government’s equivocation on climate has not sat well with leaders of the Pacific’s micro-states.

Wong’s mission appears to have succeeded on three important fronts:

- it has reassured Pacific neighbours that a new Labor government will do more than pay lip service to their concerns about climate and other issues

- Wong has made it clear Canberra will not be reticent in contesting Beijing’s influence in the region

- her mission has enabled her to assert her own authority early over the foreign policy and security reach of her portfolio.

This latter aspect will be important in how and in what form Australia responds to Chinese overtures aimed at achieving a re-set in relations.

Labor governments have long managed the relationship well

In one respect, the new Labor government has history on its side.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Canberra and Beijing.

All these years later, another Labor government has the opportunity to re-set Australia’s relations with the dominant regional player at a moment when the Indo-Pacific is undergoing profound change.

Few would reasonably argue against the proposition that a “re-set” is overdue after years of drift and ill-will under the Morrison government.

The question for Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and his national security team is how to proceed in a way that conforms with Australia’s national interest, is faithful to its values, and enables Canberra’s voice to be inserted in regional councils.

Wong has, for some time, been sketching out a more creative foreign policy approach – evident in her Pacific initiative – that will seek to expand Australia’s regional relationships and, where appropriate, take the lead in alignment with the country’s national interest.

In this sense, the joint communique on December 21 1972, signalling the establishment of diplomatic relations between Australia and the People’s Republic of China, makes interesting reading.

Unlike Richard Nixon’s Shanghai communique of 1972, which fudged the Taiwan issue, the Whitlam government document is explicit.

The Australian government recognises the Government of the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal Government of China, acknowledges the position of the Chinese Government that Taiwan is a province of the People’s Republic of China, and has decided to remove its official representation from Taiwan before 25 January, 1973.

Albanese and his security policy team can be sure this document will not be gathering dust in a Chinese Foreign Ministry archive.

China’s attachment to anniversaries is one of the more notable features of its diplomacy. These occasions may be used for political purposes, but history weighs heavily on Beijing’s foreign policy calculations.

Albanese government should jump on the promise of a thaw

When Prime Minister Li Keqiang promptly sent a congratulatory message to Albanese on the latter’s success in the recent election, Labor’s historic shift towards Beijing back in 1972 will not have been overlooked.

The wording of Li’s message was pointed. It said, in part, that China was:

ready to work with the Australian side to review the past, face the future, uphold principles of mutual respect, mutual benefit.

Beijing talks a lot about “mutual respect” and “mutual benefit”. These are phrases that are, more often that not, designed to deflect criticism of China’s human rights abuses and other bad behaviour.

But taken together with overtures for a “re-set” by the new Chinese ambassador in Canberra, Xiao Qian, Beijing has clearly decided it is in China’s interests to turn the page on a sour period between the countries.

Asked at his press conference after the conclusion of Quad talks in Tokyo about his response to the conciliatory message from Li, Albanese simply said:

I welcome that. And we will respond appropriately in time when I return to Australia.

In other responses to questions about troubled relations with China, the new prime minister has said it is up to Beijing to start removing sanctions on Australian exports.

These Albanese responses are prudent. There is no point in rushing to acknowledge such overtures. However, he would be making a mistake if he seeks to prolong what has the makings of a thaw.

He might remind himself that virtually all of Australia’s western allies, including America, have working relations with Beijing that enable officials to engage in a constructive dialogue, despite differences.

Australia’s first ambassador to China, Stephen Fitzgerald, has some wise counsel for the new government in Canberra about how to better manage relations with Beijing.

Australia under a Labor government must now return to diplomacy, talking with the PRC, for which it is ready and putting away the megaphone of gratuitous criticism, insult and condemnation which were the hallmarks of Morrison’s China policy. If we do this, there will be many issues on which we can have constructive engagement.

One of these issues can – and should – be the continued detention in China of two Australian citizens, the journalist Cheng Lei and the democratic activist Yang Hengjun. Progress towards their release should be a condition of improved relations, along with removal of punitive tariffs on imports of such items as wine and barley.

Finally, Albanese’s security policy team should pay particular attention to US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s landmark foreign policy speech delivered to the Asia Society in Washington on May 26.

In that speech, Blinken laid down guidelines for the conduct of relations with Beijing in a world whose foundations are shifting. His words bear repeating as a template for Canberra’s own interactions with Beijing.

We are not looking for conflict or a new Cold War […] We don’t seek to block China from its role as a major power […] But we will defend [the international order] and make it possible for all countries – including the United States and China – to coexist and co-operate.

Blinken’s attempts to define a workable China policy should be regarded in the same vein as another important statement delivered 17 years ago by then Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick in New York. In that speech, Zoellick said:

We now need to encourage China to become a responsible stakeholder in the international system.

Blinken’s and Zoellick’s interventions, two decades apart, are important guardrails for a constructive relationship with China.

Source: The Conversation