- The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade last year closed two bodies monitoring its US$3 billion overseas aid programme, which has focused on the region as Beijing’s influence grows

- While it said the bodies’ ‘core functions’ would continue, the document shows staff were cut and ‘strategic evaluations’ entirely removed, prompting criticism from aid groups and scholars

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) in September said it had closed the Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE), an independent arm tasked with monitoring the outcomes of Australia’s A$4 billion (US$3.06 billion) overseas aid programme, which has ramped up its focus on the Asia-Pacific amid

While aid groups and analysts at the time criticised the move as shortsighted, DFAT downplayed the changes as a “slightly refreshed approach to monitoring and evaluation” following the reallocation of hundreds of millions of dollars of funding towards pandemic recovery efforts in the Asia-Pacific.

“I can absolutely assure you that robust monitoring and evaluation of our development programme is still a top priority for this department,” Klugman said.

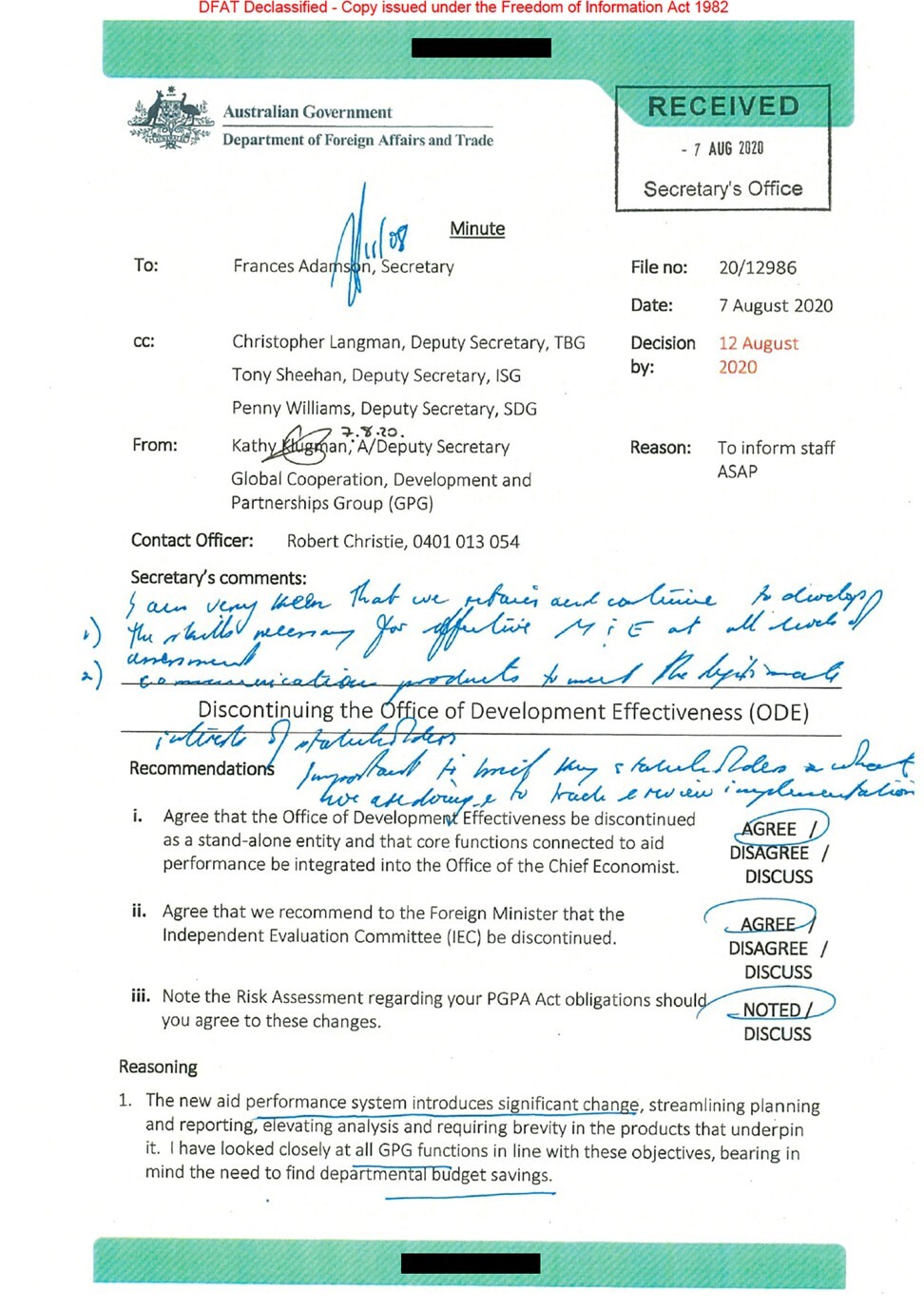

But a DFAT minute obtained exclusively by This Week in Asia reveals the department had in early August decided to cut the ODE’s staff from 13.5 full-time employees to five, and do away entirely with the office’s role of carrying out “strategic evaluations”, one of its three key functions.

The minute, sent by Klugman to DFAT Secretary Frances Adamson, makes explicit that the “need to find departmental budget savings” was a key driver of the decision to scrap the oversight bodies.

“ODE’s strategic evaluations were a valuable contribution but do not form part of the aid programme’s performance assessment,” said the minute, dated August 7. “The pace of change and pressure on posts mean that ODE’s programme of large evaluation is no longer sustainable.”

Despite committing billions of dollars to a “Pacific step-up” widely seen as aimed at countering Beijing’s growing influence in the region, Australia’s total spending on diplomacy and aid fell from 1.5 per cent of the national budget to 1.3 per cent between 2013 and 2019 – a drop in pure dollar terms from A$8.3 billion to A$6.7 billion, according to the Australian Institute of International Affairs.

The DFAT minute, the recommendations of which were signed off on by Adamson before going to foreign minister Marise Payne for final approval, also shows that the department decided to scrap the Independent Evaluation Committee (IEC), an external oversight body sitting above the ODE, weeks before Klugman told parliament she was not in a position to give “any definitive advice” about the committee’s future.

In addition to savings from reduced staff, scrapping the ODE’s strategic evaluations and the IEC would cut annual costs by A$800,000 and A$100,000, respectively, the minute said.

The document, obtained under freedom of information laws, also highlighted the importance of a “communications plan” and briefing “key stakeholders” about the changes, although aid groups and scholars complained of being totally blindsided by the reorganisation after it emerged in parliament.

Stephen Howes, director of the Development Policy Centre at the Australian National University, said less resourcing for evaluation was dangerous, especially in light of Canberra’s recent moves to boost spending.

“The memo shows no consideration of the damage that would be done by abolishing ODE’s and IEC’s leadership roles in Australian aid evaluation,” said Howes, who contributed to the 2006 Australian Aid White Paper.

Marc Purcell, CEO of the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID), the peak body for Australian NGOs involved in the sector, said it was unclear how Canberra would ensure the transparency and effectiveness of its aid programme in the future.

“Effective development is a key foreign policy tool,” he said. “Never before has it been more important to make sure scarce taxpayer money is spent for maximum impact. ODE and IEC’s key role was to do just that – measure impact, and make sure our development dollar goes further.”

Purcell added that ACFID was “dismayed at the decision late last year to abolish the ODE and the IEC – we were not consulted as part of this decision and were informed well after the fact.”

Pat Conroy, shadow minister for International Development and the Pacific, accused the government of undermining Australia’s development programme “at a time of profound regional geopolitical challenges”.

“[These moves] mean Australia is not only doing less to help lift people in developing countries out of poverty and disadvantage,” Conroy said. “They also diminish Australia’s standing in the Asia-Pacific and allow other regional powers to fill the gaps created by the Morrison government’s aid cuts, particularly in Southeast Asia where the cuts have fallen hardest.”